The history of the Hanbury Botanic Gardens

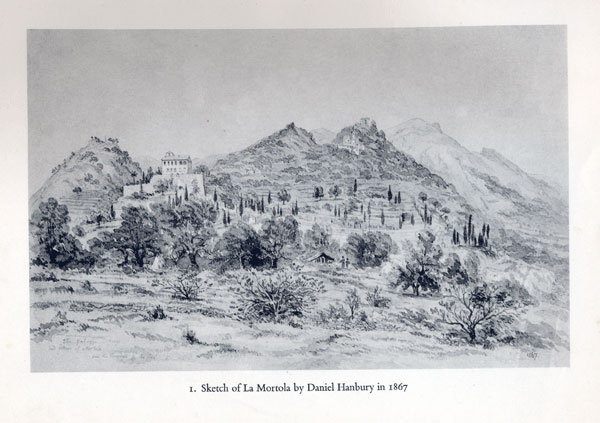

Thomas Hanbury, after having purchased the enchanting farm of the Orengo family located in Mortola, in 1867 began the extraordinary work that would make his property one of the most famous gardens in the world.

Drawing by Daniel Hanbury from 1867

Thomas's brother, Daniel Hanbury, took a decisive part in the transformation, providing the scientific basis for the planting of the acclimatization garden, the dream that the two gentlemen cherished since their youth. The first rose plants were brought in in the autumn and came from his father's garden at Clapham Common; at the same time they were bought by the Huber nurseries in Hyeres, Nabonnand in Golfe-Juan and by the Thuret garden in Cap d'Antibes. The following year, the plants were brought in from Paris, Montpellier and Kew, also thanks to relationships with scientists, directors of botanical gardens and plant traders. Already in the early years, the collections of South African, Australian and American plants attracted the attention of the scientific world at an international level. The plants in the gardens were not only considered in their nursery and exotic aspect, but were also the subject of pharmacological research and studied for their economic importance. In 1868 the agronomist and landscape architect Ludwig Winter became curator of the gardens. The area occupied by the gardens is characterized by a substrate of nummulitic limestones. They give rise to a difficult, compact terrain, easily eroded by rainwater and brackish winds. Species such as rhododendrons, camellias and azaleas do not like this type of soil. There is also a limited travertine area, which gives rise to a sandy soil, excellent for cultivation, for example of the Melaleuca genus. Thomas, Daniel and Winter thus had to solve the problem of soil runoff due to the autumn rains with important soil modeling interventions; they also had to prepare irrigation systems that would allow them to face the summer droughts.

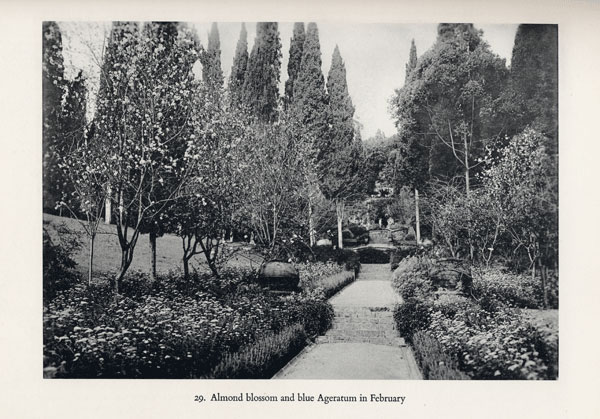

Almond trees in bloom

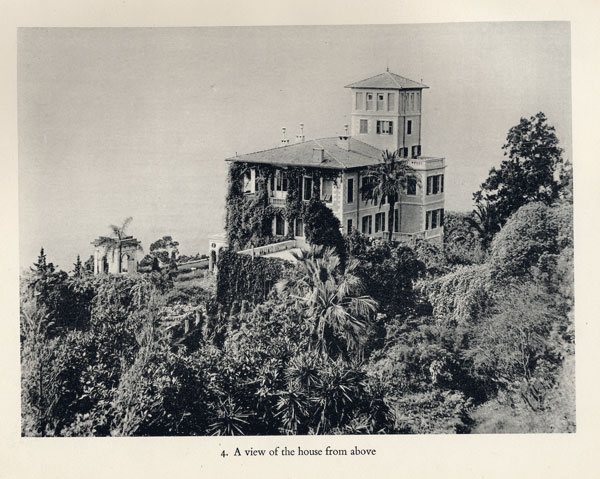

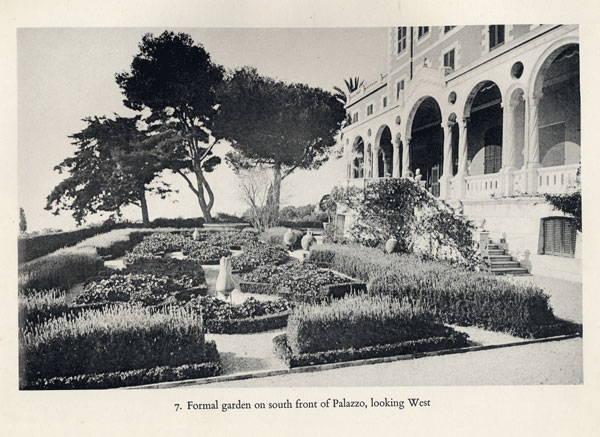

The interventions also concerned the reworking of the routes, the restructuring of Palazzo Orengo and the other buildings on the property, the architectural ornamentation of the gardens.

Orengo Palace

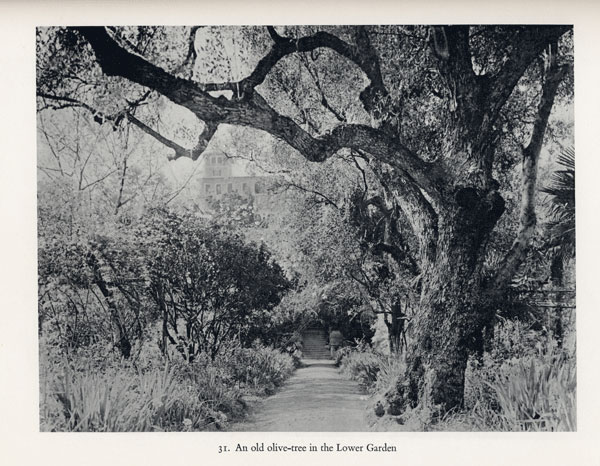

The property had an enormous wealth of microclimates derived from different exposures to light and wind, from different slopes and humidity conditions. The two brothers and their precious collaborator knew how to make the most of them, recognizing the most favorable conditions for the growth of the plants they wished to cultivate. So between the sea and the ancient Roman road, in addition to the old olive grove, they placed the citrus grove, the vegetable garden and the rose garden, sheltered from the saltiness by a renovated boundary wall. The Australian forest was placed on the gentle slope above the Roman road, while citrus fruits were still cultivated below the villa. Even higher up, the olive grove was maintained, while the species of the Mediterranean maquis were taken care of to the west and east. Along the rio Sorba, species of humid environments were placed. It was then Winter who organized the maintenance of the nurseries, the collection of seeds and trained the local staff who had to work in the gardens. Thomas, who married Catherine Aldam Pease in 1868, with whom he had four children, from 1874 spent the winters at Mortola. The following year, when his brother died, Thomas remained alone in organizing the management of the gardens. Valuable botanists from Germany such as Gustav Cronemayer, Kurt Dinter and Alwin Berger were called to his direction. In 1907, when he died, the Hanbury Gardens were an active, splendid and fruitful reality.

Avenue of olive trees

After Thomas's death, his wife never returned to Mortola and the period of the First World War, with the return of the last curator Alwin Berger to Germany, marked an era of serious deterioration. At the end of the conflict it was Thomas's eldest son, Cecil, who decided to put his hands back on the property. He undertook an impressive job of restructuring, maintenance, reorganization, restoration, new enrichment of the building, nursery, scientific, historical and artistic heritage. Cecil's political commitments meant that everything fell on his wife, Lady Dorothy, who dedicated herself to it with passion and competence. Cecil continued to take care of the scientific reports and the general organization of the property, Dorothy was responsible for the new interventions, over which she had complete autonomy. Dorothy enlisted the help of her father, John Frederic Symons-Jeune, a well-known landscape architect and her brother, Captain Bertram Hanmer Bunbury Symons-Jeune known for his rock garden designs and his books on 'subject.

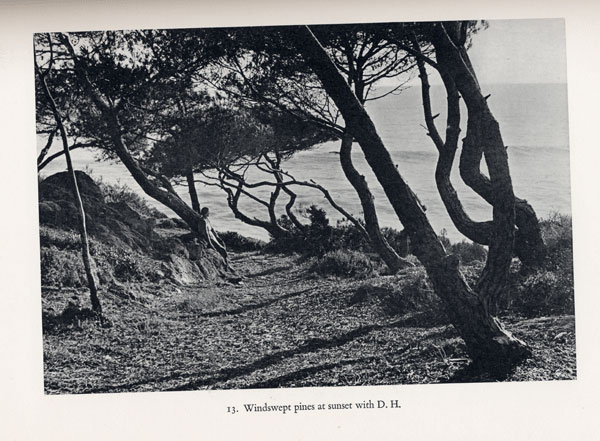

Dorothy Hanbury in the pine forest at sunset

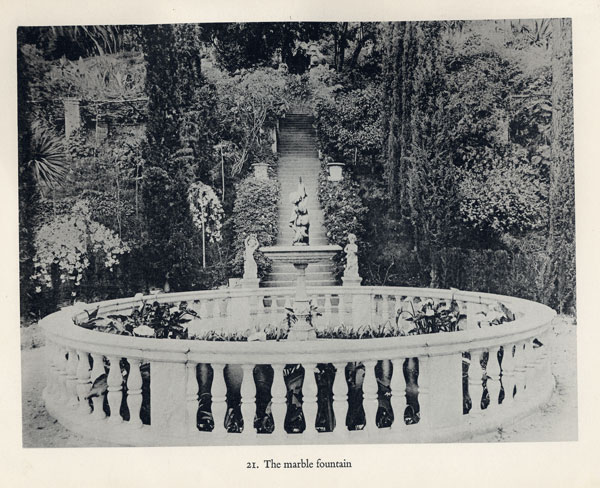

This is the period in which the different areas of the gardens begin to be identified with numbers, a method which makes the identification of botanical specimens more immediate, to modify the central part of the gardens and to give more space to the landscape aspect, creating panoramic views, other avenues, driveways, fountains, as required by the new taste that was taking hold on the French Riviera, as described in the Hortus Mortolensis in 1938.

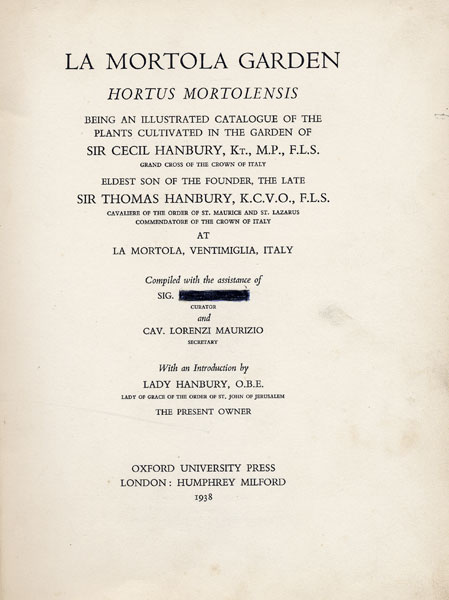

Hortus Mortolensis catalog of 1938

The scientific aspect continued to be cultivated thanks to relationships with numerous gardens and botanical gardens from all over the world, the hospitality of students from the School of Horticulture promoted by Kew Gardens, the exchange of specimens and seeds, the enrichment with new species from from Mexico, Chile, South Africa, India, places where Cecil financed botanical expeditions. The curators in this period were the English Joseph Benbow and McLeod Braggins and were followed by Italian directors trained in Great Britain.

Marble fountain

The Gardens maintained their character as a political and cultural center and continued to be open to the public. The Superintendence bound the property recognizing its architectural, landscape and cultural value, a bond ratified by Law 1089 of 1939. Dorothy lived at the Mortola even after Cecil's death in 1937, but in 1940 the Gardens, belonging to foreigners, were confiscated and entrusted to Banco di San Paolo.

South terrace

During the Second World War, the Gardens, first occupied by Italian troops, then by German troops, suffered very serious damage. 1944 was the black year of the property which was bombed, looted and, of course, abandoned. In 1945 Dorothy managed to return and with just twenty gardeners she began the rebuilding work, supported by her second husband the Reverend Rutven Forbes. But the work proved superior to Dorothy's economic strength, who after several unsuccessful attempts to find supporters of her effort, in 1959 resolved to ask for help, during the Montreal IX International Congress of Botany, to protect the property from probable speculation. The Congress spoke to the Italian State of the state of deterioration of the Gardens and their immense cultural value, hoping for their purchase, which would have made the area public, protected and maintained in its scientific purposes. Thanks also to the intervention of the Istituto di Studi Liguri, in 1960 Lady Dorothy sold the Mortola complex to the Italian State. Ratification took place in 1962 and the gardens were entrusted to the Istituto di Studi Liguri. The implementation of the program drawn up by the Director of the Institute, Nino Lamboglia, a man of great breadth and profound scientific, didactic and cultural commitment, had to be staggered over the years due to the deterioration situation that Onorato Masera, appointed director, had to face: he began the cleaning work, tillage, reconstituted the nursery, the sowing of thousands of plants, the exchange of seeds with botanical institutes. But still the difficulties were not finished; in particular the onerous economic commitment, aggravated by other contingent problems, forced the Institute to renounce the commitment undertaken in 1979. The Gardens were managed by the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and then by the Superintendency for Environmental and Architectural Heritage of Liguria. The 1980s marked a period of reorganization of the Gardens and new interventions aimed at restructuring the property: the Superintendence promoted the restoration of the villa, began some interventions on the other buildings, fenced off the area, intervened on the water and electricity systems, rebuilt retaining walls.

In 1983, was concluded the agreement which entrusted the management of the Gardens to the University of Genoa which, however, was only able to start operating in 1987, when the document was officially transmitted. With Regional Law 31 of 2000, the Liguria Region established the "Hanbury Botanical Gardens" Regional Protected Area and in 2002 university management, also reconfirmed by the Regional Law, became more organized with the establishment of a University Services Centre. Today the 18 hectares of Hanbury Gardens are experiencing a period of lively activity with the implementation of numerous projects which are progressively bringing the complex to the architectural and landscape splendor it possessed in the 19th century and to an international value and scientific activity.